| |

The scope and purpose of the web catalogue

|

A web catalogue of a major collection of medieval illuminated manuscripts

must aim to serve many different masters. Just like a published catalogue,

it should provide information to anyone with a serious scholarly interest.

Like a public exhibition, however, it should also be interesting and pleasurable

to the occasional visitor, merely keen on finding pretty pictures.

Of course, we have tried to make the access to the underlying database

of medieval illumination as transparant as possible. Therefore, the

search screen will hold few surprises for those who are used to consulting

catalogues on medieval manuscripts. Even so, it may still be useful

for them to read at least part of this prologue. For those who have

no experience with manuscript catalogues or with medieval art in general,

these introductory paragraphs will certainly be useful, because we shall

show something of the richess of the material. We hope that the type

of information we describe here will stimulate you to explore the online

catalogue which you will reach when you click search.

For the moment the web catalogue is first of all committed to offering

a search facility for the collection. This emphasis on the database and

its access should not prevent you from browsing around. As a starting

point for browsing through the collection you could, for example, simply

select a Shelfmark from the first index on the search screen. It

is our intention to supplement the search facility of the catalogue with

a browse option which will give access to 'temporary exhibitions'

that focus on particular aspects of the collection.

|

|

Subject matters

We begin with a few notes on the iconographic retrieval facilities of

the catalogue, because the illumination is a focal point of the collection,

and because a great deal of time and effort has been invested in the subject

access to the miniatures, initials and border decorations. First of all,

captions have been written for every picture and an alphabetically arranged

list of these captions can be called forth by clicking on the index button

at the box Iconographic descriptions.At a later stage of the project

a complete list of the words used in the captions will be added to the

retrieval facilities.

Secondly,

all pictures have been indexed with the help of the system for iconographic

classification Iconclass.General information about Iconclass

can be found at the

Iconclass website. More specific information about the way the Iconclass

system has been applied to these manuscripts and about a number of editorial

issues, can be found at the website

of the indexers. Secondly,

all pictures have been indexed with the help of the system for iconographic

classification Iconclass.General information about Iconclass

can be found at the

Iconclass website. More specific information about the way the Iconclass

system has been applied to these manuscripts and about a number of editorial

issues, can be found at the website

of the indexers.

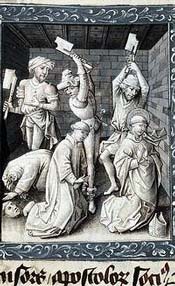

As you will find out when you use the catalogue, the application of Iconclass

makes it possible to query the database in a very precise way. Should

you be drawn to the gothic detail, for example, you could query the database

for pictures showing the detached heads of victims of decapitation. This

would retrieve, among others, the scene from Maccabees, where the head

of Alexander Balas is cut off and offered to King Ptolemy IV (left), and

the famous martyrdom of St. Denis and his companions (right).

At the same time the hierarchical structure of Iconclass allows you to

make very broad thematic selections. Whether you are interested in representations

of stories from classical history or mythology, agricultural activities,

the signs of the Zodiac, or scenes from the life of Christ between the

Last Supper and the Crucifixion, they can all be easily extracted from

the database with the help of the concepts that are part of Iconclass.

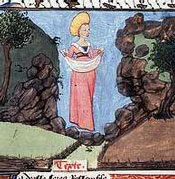

Below we give a sample of the query results for the general Iconclass

concept 47I agriculture, cattle-breeding, horticulture,

flowerculture, etc.. On the left you see a picture of Ceres - goddess

of the 'cultivated earth' - sowing wheat, from a copy of l'épître

d'Othéa by Christine de Pisan. In the centre there are two

pictures of farmers from the so-called labours of the month cycle

of a calendar in a Book of Hours. On the right is an illustration from

Livy's Roman History, of the story of Spurius Maelius who provisions the

city of Rome with wheat during a famine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chronology and geography

An important question about any historical document is of course: where

and when was it made? Obviously, then, places of origin and dates

of production have been made searchable. Since only a limited number of

manuscripts contain exact information about their year of production,

the option to search a date range - e.g. "all manuscripts made between

1250 and 1300" - is an important one and therefore included here.

The analysis of manuscripts to establish where they were made is, of course,

an ongoing scholarly effort. To stimulate that effort is one of the reasons

the collection is offered to the scholarly community in this way. Given

the limitations of the project and the scope of the collection, the names

of cities, regions, dioceses, convents, etcetera, could not be incorporated

in a hierarchy of historical geographical names. Only one top level broader

term could be included for each Place of origin. These broader

terms, which are best used to limit certain queries, are: France,

Northern Netherlands, Southern Netherlands, Italy,

Germany, Great Britain, and Spain. The geographical

division of the collection is not very surprising: about 90% of all manuscripts

can be divided in three large groups, attributable to the present Netherlands,

Belgium, and France. Of the remaining 10% or so, seventeen are Italian,

six are German, two English, and one is Spanish, recently acquired with

the financial support of the 'Friends of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek'.

|

This

Spanish manuscript is a Book of Hours, made in Valencia around 1460.

Its illumination is attributed to 'followers of Juan Mari'. On the left

is shown the Annunciation scene, with which the Hours of the Virgin

begin. This

Spanish manuscript is a Book of Hours, made in Valencia around 1460.

Its illumination is attributed to 'followers of Juan Mari'. On the left

is shown the Annunciation scene, with which the Hours of the Virgin

begin.

On the right you see a grisaille with the same subject, this time

from a Delft Book of Hours, datable between 1440 and 1460 and attributed,

apt but not too original, to the so-called 'Masters of the Delft Grisailles'.

Here too, the Annunciation is the opening illustration of the Hours of

the Virgin.

Since the web catalogue also allows you to add the title of the text which

is accompanied by an illustration, to your query conditions, combined

searches for iconography, date, location, and text can be executed.

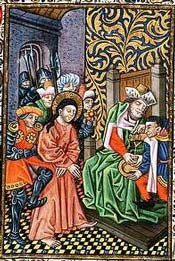

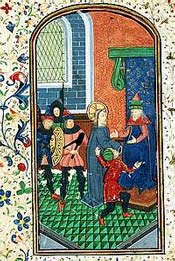

In this way you may discover, for instance, that out of forty six manuscripts

with the Hours of the Virgin with an illustration for the hour of Prime,

forty are illustrated with scenes from the Nativity cycle. Six of them,

however, are illustrated with a scene from the Passion, namely Christ

before Pilate. Half of these six originate in Utrecht, the other half

in the Southern Netherlands. Four of them are shown below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Utrecht, precursor of the Masters of Zweder van Culemborg, circa 1425

|

Utrecht, Master of the Boston City of God, circa 1470

|

Southern Netherlands, circa 1430-1450

|

Southern Netherlands, Willem Vrelant, circa 1460

|

|

Workshops and artists

Of the four miniatures of Christ before Pilate shown above, three

are attributed to a master. Only one of these is identified by a 'real'

name, Willem Vrelant. The others are identified with what is actually

a name for a set of stylistic characteristics. At   the time of writing over 1600 individual illuminations of the collection

have been attributed to 63 different stylistic groups and masters. Another

30 or 40 names of masters, workshops, etcetera, are still waiting to

be linked to specific miniatures, initials and border decorations. These

names can be selected from the indices on Miniaturist

the time of writing over 1600 individual illuminations of the collection

have been attributed to 63 different stylistic groups and masters. Another

30 or 40 names of masters, workshops, etcetera, are still waiting to

be linked to specific miniatures, initials and border decorations. These

names can be selected from the indices on Miniaturist

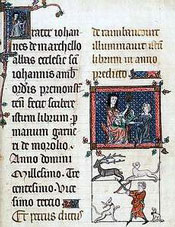

A limited number of the illuminated manuscripts of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek

carry the name of their scribe and an indication of their date of production.

Much rarer still, are manuscripts that carry their date of production

in combination with the name of their illuminator. On the left is a page

signed by Spierinck, and dated 1498. On the right you see the colophon

of a missal which says that Garnerus de Morolio wrote this manuscript

and Petrus de Raimbaucourt illuminated it 'illuminavit istum librum'.

They did this in 1323 for Johannes de Marchello, abbot of the Premonstratensian

abby of St. Jean in Amiens.

|

|

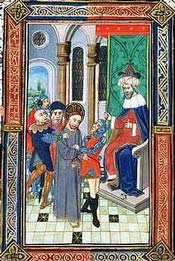

Nobles and antiquarians: the provenance

of the collection

Scribes

and the occasional illuminator are not the only ones to have left behind

evidence of their activity and presence in manuscripts. Owners did so

too, by marking their possessions in various ways. The simplest way

to do this would be, like you would do today, to write your name on

a fly-leaf. A much more elaborate way would be to have your portrait

painted in the book. Thus you could document your role as a patron.

Such a portrait is shown on the left, where Augustin Molinet offers

his prose translation of the Roman de la Rose to Philip of Cleves.

Notice the little mill in the background, a visual pun on Molinet's

name. Scribes

and the occasional illuminator are not the only ones to have left behind

evidence of their activity and presence in manuscripts. Owners did so

too, by marking their possessions in various ways. The simplest way

to do this would be, like you would do today, to write your name on

a fly-leaf. A much more elaborate way would be to have your portrait

painted in the book. Thus you could document your role as a patron.

Such a portrait is shown on the left, where Augustin Molinet offers

his prose translation of the Roman de la Rose to Philip of Cleves.

Notice the little mill in the background, a visual pun on Molinet's

name.

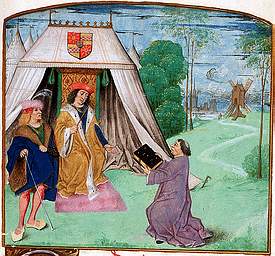

Like

other bibliophiles, Philip also had his coat of arms added to existing

manuscripts, e.g. to the copy of Livy's Roman History, which

entered Philip's library via his wife Françoise de Luxembourg,

and of which a fragment is shown on the right. Like

other bibliophiles, Philip also had his coat of arms added to existing

manuscripts, e.g. to the copy of Livy's Roman History, which

entered Philip's library via his wife Françoise de Luxembourg,

and of which a fragment is shown on the right.

|

|

With

Philip of Cleves (1456-1528) we have mentioned a source of one of the

core collections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, and the collection

that would give it with its name, i.e. the collection of the stadholders,

forefathers of the royal family of the Netherlands. With

Philip of Cleves (1456-1528) we have mentioned a source of one of the

core collections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, and the collection

that would give it with its name, i.e. the collection of the stadholders,

forefathers of the royal family of the Netherlands.

Inevitably, the history of how the circa 330 illuminated manuscripts

that are presented here, came to rest in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek

is a chequered one, as you can see when you consult the index of Former

owners or institutions. The story of the stadholders' collection

is only a chapter in it. Another substantial chapter has to do with

a large group of manuscripts added to the Library's collection in 1823

by king William I. This group of 168 manuscripts had been part of the

rich art collection of the eccentric Belgian nobleman J.D. Lupus. The

king had paid 20,000 guilders for it, shortly after 1817. Although 20,000

guilders was a substantial sum, the king struck a very good deal if

we take into account that some 20% of all miniatures, initials and border

decoration in the web catalogue are from the Lupus collection. On the

right you see an opening from one of the manuscripts from the Lupus

collection, not selected because of its quality, but because it bears

curious marks - 17th-or 18th-century painted borders - of the usage

by one of its later owners, that gives yet another meaning to the term

'amateur'.

|

Limitations

This prologue to the web catalogue should of course also warn you about

its limitations. In other words, it should inform you about some of

the things you will not find here, at least not at this moment.

The emphasis of the catalogue is, to put it somewhat paradoxically,

on book illumination, not on illuminated books. Obviously, information

is made available about the manuscripts themselves, as is evident when

you look at the left half of the query screen. But none of the manuscripts

has been photographed in full, e.g. to offer a full electronic facsimile

of its text. Codicological and palaeographical idiosyncracies fell outside

the scope of the project. The pen-drawn decoration - an important tool,

especially for the location of manuscripts from the Northern Netherlands

- could at present not been given the attention it deserves. The information

supplied about bindings could not at this time be supported with visual

material.

As has been said above, information about the choices that had to be

made regarding the subject access to the pictures, can be found on the

website of the indexers. Here we limit ourselves to showing two of the

marginal illustrations that could not, given the present limitations,

be included in the iconographical information of this web catalogue.

|

|

|